The VC Fund Trap: 2025 - 2030

Between the small and the elite lies a trap, or in other words, the precarious middle ground, where funds neither secure the best access nor optimise for ownership and entry price.

Venture capital success often follows two distinct trajectories: small, nimble funds that leverage quantitative discipline and qualitative alignments and access-driven giants, which dominate with networks and resources. While both approaches have well-trodden playbooks supported by data, a looming gap is emerging between them. This divergence, which I term the ‘VC Fund Trap’, will arise when funds fail to optimise for ownership, lack the influence to secure premium deal access and ultimately risk sliding into irrelevance.

Mathing the Math: Quantitative Advantages

Smaller funds can derive an edge from meticulous portfolio construction. For instance, a $100 million fund targeting 10% ownership in early-stage ventures can achieve great returns with sub-$10 billion exits. Over the past seven years, there have been 50 venture-backed exits surpassing $10 billion — while such outcomes are conceivable, they are far less frequent than optimistic Excel projections might suggest.

Ownership dynamics highlight the challenge for larger funds: each $10 million raised by a fund typically buys 1% ownership in the early stages. Once a pre-seed/seed investor exceeds a $100 million fund, optimising for ownership becomes more challenging. Larger funds face two options: deploy more capital per company, thereby requiring larger exits to maintain returns, or expand their portfolio size, which introduces risks related to focus, execution, and reserve management.

Larger funds often overpay to meet ownership thresholds, locking themselves into exit requirements that are quantitatively more challenging to achieve. By contrast, smaller funds can outperform simply by optimising for entry economics and achieving smaller, realistic outcomes.

LP/Founder: Top-to-Bottom Alignment

As an LP, we must consider the type of risks we incentivise and the relationship between GPs and founders we are investing in. When things get tough, as they inevitably do, are both sides of the table similarly incentivised to reach an optimum outcome? Smaller funds work closely with their portfolio, taking a company-building approach over capital allocation. We must continue to back those running for the 20 (carried interest) instead of walking for the two (management fees). It creates better collaboration, not just between LPs and GPs, but a full top-to-bottom alignment between LP and founder.

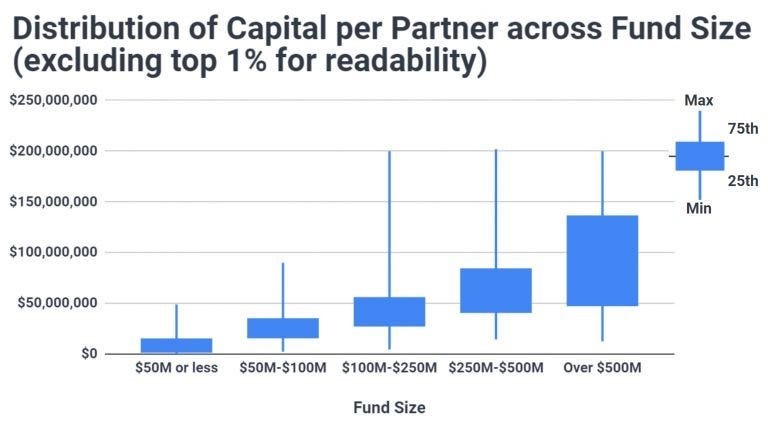

The growing disparity between smaller and larger funds becomes even clearer when examining capital managed per partner, and average compensation structures. For funds under $50 million, the management fee per partner per fund is typically $1.9 million, whereas for funds exceeding $500 million, it swells to $26 million. Asset-accumulating VCs have gamed the traditional fee structure and created massively misaligned incentives. GPs in outsized funds can create astonishing wealth without being meaningfully invested in the outcome of their portfolio. It raises several questions: where is the incentive to stay small, and can LPs do more to avoid the spiral?

Outperformance: Small is Beautiful

There’s plenty of performance data that lends itself to this side of the argument. Although comprehensive financial data in private markets is inherently limited, existing figures paint a telling picture. The chances of delivering a 5x fund diminish dramatically as fund sizes increase: 11.2% of funds sized $0–30m, 7.5% for funds sized $30- 100m, 7.0% for funds sized $100–250m, and only 1.3% chance for funds $500m+ (PitchBook). That’s a 10x greater chance of higher returns from the smallest to largest fund size. And while there is less performance data for small funds (5.1% vs 16.8% — per cent of funds raised, VenCap), the difference is not 10x. One could argue that even with survivorship bias, the data still looks advantageous for ‘Team Small’.

When visualising the performance data from over 3,000 VC funds, spanning four decades and many market cycles, as seen below, it becomes evident that the trend is linear.

The Access Card: The Top 10–20

At the other end of the spectrum are the elite firms — household names like Sequoia Capital, Andreessen Horowitz, and Index Ventures — that aim to dominate through access. The top firms typically see the best repeat founders, albeit often competing on price. These firms wield influence beyond investing, lobbying governments to drive systemic change and influence industries, such as nuclear energy, and tilt markets favourably.

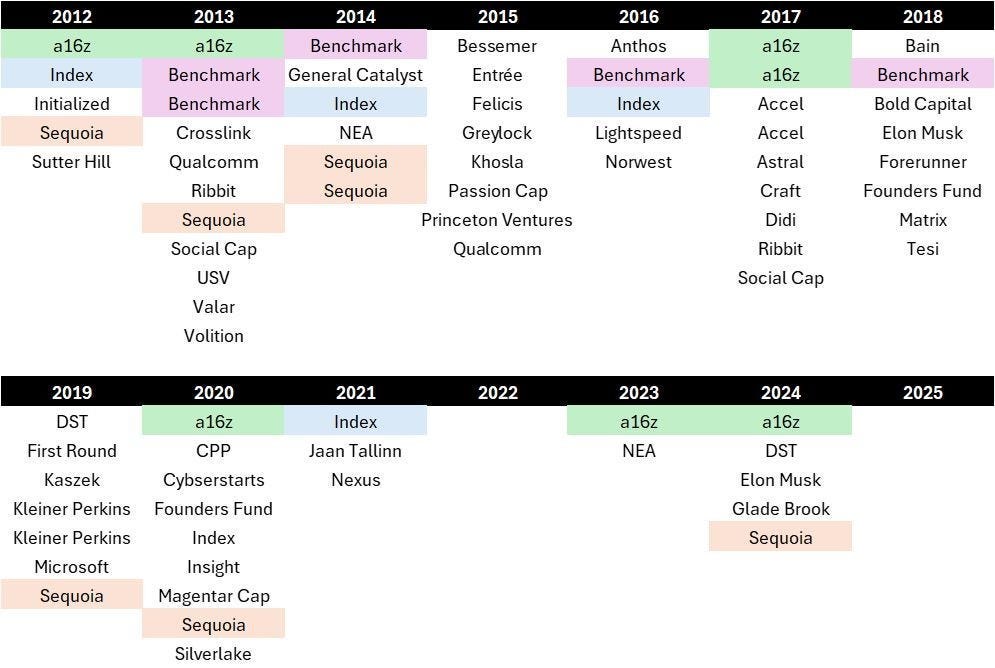

There is a power law in venture where 99% of deals are noise, and an astute VC’s job is to find a needle in each year’s haystack. The elite have earned the access card by showcasing the largest outcomes most often. The following VCs invested in the Series A rounds for companies that would go on to achieve $5 billion-plus valuations: Andreessen Horowitz (7), Sequoia Capital(6), Benchmark (5) & Index Ventures (4). When we talk about outliers, this is a pretty good visual representation. Special shout out to Benchmark for keeping fund sizes respectable.

The Math isn’t Mathing? The Carried Interest Multiple

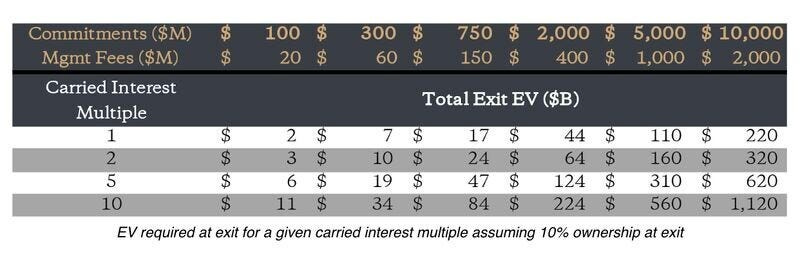

Despite their dominance, the elite face new challenges. For a $10 billion series of funds, the firm will pull in $2 billion worth of management fees. To merely double compensation through carried interest, the firm would require $220 billion of collective exit value. Owning 10% of $220 billion at a time when positions are liquid would be an unprecedented achievement for any venture capital firm.

There has never been a US VC-backed company that has IPO’d or been acquired for over $100 billion, and only two private companies (OpenAI and SpaceX) have cleared that hurdle in private, outside-led financing rounds. If a $10 billion exit is considered a ‘grand slam’, the elite will need an astonishing ability to repeatedly select winners and negotiate sufficient ownership. Simply put, to make $2 billion, these GPs need to show up for work. To make another $2 billion in carried interest, it would have to accomplish a feat that no one has ever come close to achieving. That LP/founder alignment is suddenly looking a little different.

The VC Fund Trap: Zombie Funds Between 2025–2030

Between the small and the elite lies the trap, or in other words, the precarious middle ground, where funds neither secure the best access nor optimise for ownership and entry price. Unlike small funds, mid-to-larger funds will struggle to optimise ownership due to their size. These firms cannot rely on smaller exits to generate meaningful returns and must aim higher, but without access to top-tier assets, they are stuck in a no-man’s-land. Without the elite’s ability, they are locked out of the best deals. It limits upside potential and further exacerbates the clearer picture of a portfolio of subpar or overpaid assets.

Many of these funds risk becoming ‘zombie funds’ — vehicles that fail to raise new capital or deliver returns and become stuck in limbo. We are about to see a new wave of such funds, neither successful enough to compete with the elite nor small enough to possess the associated quantitative and qualitative advantages.

2025–2030: Where We Go from Here

Future outperformance via small funds requires the right manager selection. While identifying historically successful firms is straightforward, their ability to generate unprecedented levels of exit liquidity remains unproven. Do you take on selection or execution risk? There are good arguments for both. The real challenge lies with those funds that do neither; those who can’t optimise for construction and don’t have the access cards. These are the firms most at risk of becoming relics of a bygone era.