The lore is well known: Venture is a power law game. One breakout can return an entire fund. What’s less often said (but equally critical) is just how much the size of that fund determines whether the breakout actually moves the needle.

Size Matters. But So Does Selection.

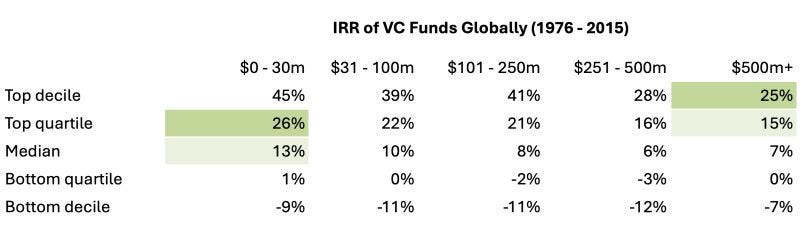

Data from 1,700 VC funds reveals a very simple (and very strong) correlation—the smaller the fund, the better the performance. However, the quantum of funds increases, too, so a selection risk must be underwritten.

Fund size is a pivotal and often misunderstood feature of venture strategy. Running counter to the prevailing narrative, where larger funds are hailed as evidence of success, the median fund size of top quartile funds in the last decade is $65M. That number drops further to a mere $38M for top decile VCs. In an ecosystem that often equates “bigger” with “better,” this is a counterintuitive truth. At a fund size of sub $70M, these GPs are not headlining conferences or raising $1B+ vehicles; what they are doing, however, is delivering the true VC returns LPs expect when allocating to Venture.

The logic, while surprising, is straightforward and rooted in both math and operation structure: it's exponentially easier to return a $50M fund than a $500M fund. A $200M commonly sized venture exit might be a career-defining outcome for a small fund. For a mega-fund, it barely moves the needle. Smaller funds can afford to move earlier, act faster and optimise for ownership in a way large, AUM-driven funds simply can't.

Lest we all start investing solely into sub $100M funds, there is a huge caveat to be considered here; none of this matters if you're not in the right funds.

I have said this time and time again, and I will continue to ad infinitum: Access is everything. Venture outcomes are not evenly distributed. In the next decade, the top 5% of managers will outperform by staying focused, sticking to their niche, and not scaling for the sake of it. The key is putting a great selection mechanism in place.

The best funds are not solely chasing AUM—they’re chasing alpha.

“Small Fund” Strategy Works

This logic, in turn, becomes pivotal to emerging managers. The median new venture firm in 2015 was $20M. In 2024, it was still just $24M. Whilst the average fund size in that time has ballooned to $170M, largely due to the emergence of mega-funds, most new managers are still playing in the same lane. Despite the ballooning average, the fact that the median has remained flat suggests one thing: alpha returns haven’t needed to chase size because strategies in smaller funds work.

Market consolidation has been a defining theme of 2024, with six firms raising 50% of the capital. Large multi-stage firms are pushing up entry prices, including at the earliest stages. In our own deal flow, we are seeing seed rounds this year exceeding $10M, often priced at $30–50M post-money.

At first glance, this might seem like a sign of strength: capital abundance, founder confidence, institutional backing. But beneath the surface, the math begins to shift. For managers not participating in these rounds through a large, multi-stage strategy, the implications are clear: you’re underwriting late-stage valuations without the corresponding downside protections. In a portfolio where ownership and cost basis drive returns, this dynamic introduces asymmetry. What looks like seed may increasingly feel like Series A, however, without the commercialisation or governance rights to match.

Back The 20. Not the 2.

The main takeaway of this? Keep backing the GPs running for the 20 instead of walking for the 2. Not only are they a vital part of a healthy venture ecosystem, but they’re also optimising for ownership, portfolio construction, and, most importantly, for founders. Their success depends on it. For LPs, this means resisting the gravitational pull of headline fundraises and instead doubling down on backing smaller, harder-to-access managers off-cycle.

In venture, smaller really can mean smarter—but only if you’re backing the smartest people.

Interesting. Why did you stop in 2015? According to PitchBook, the last 10 years have been the worst in venture capital performance history. It would be interesting to see how those numbers have shifted since then.

The asymmetry here is everything: small funds have to be selective, while large funds often can’t afford to be. Love how this surfaces that quiet discipline.