Big Funds, Bigger Problems: The Flawed Math of Venture at Scale

Venture capital has long been a game of outliers, where success hinges on identifying and backing a select few companies that achieve extraordinary outcomes — effectively driving the bulk of a fund’s returns, while the majority of investments fall short. However, as fund sizes have expanded, so too has the challenge of delivering the level of returns necessary to justify the inherent risk this ‘Power Law’ poses.

At a certain scale, the math starts working against investors; even if and when it can be overcome, the incentives that drive venture capitalists — the very things that push them to go to war alongside founders — begin to erode.

This is the fundamental challenge of large funds, forcing their investors into a game that has yet to be successfully mastered.

The Rule of 32

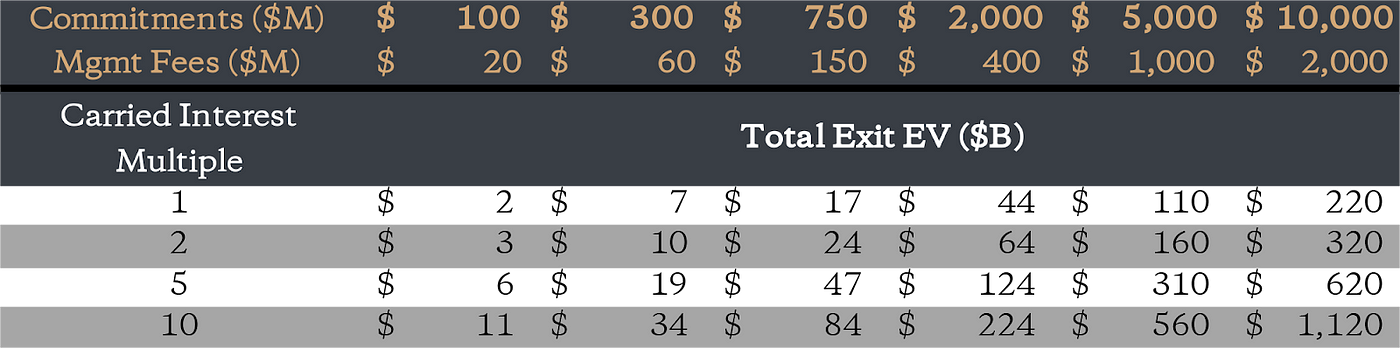

There’s a simple way to think about what it takes to return a venture fund: multiply its size by 32. That’s the total exit value needed to generate a 3x net return, the level that most venture portfolios should be underwritten to.

Rule of 32: Multiply a fund (or series of funds) by 32 to determine the required total exit value needed to achieve a 3x net return.

For a $5 billion series of funds, this translates to requiring $160 billion in exit value from its outliers — all while maintaining a 10% ownership stake at the point of exit.

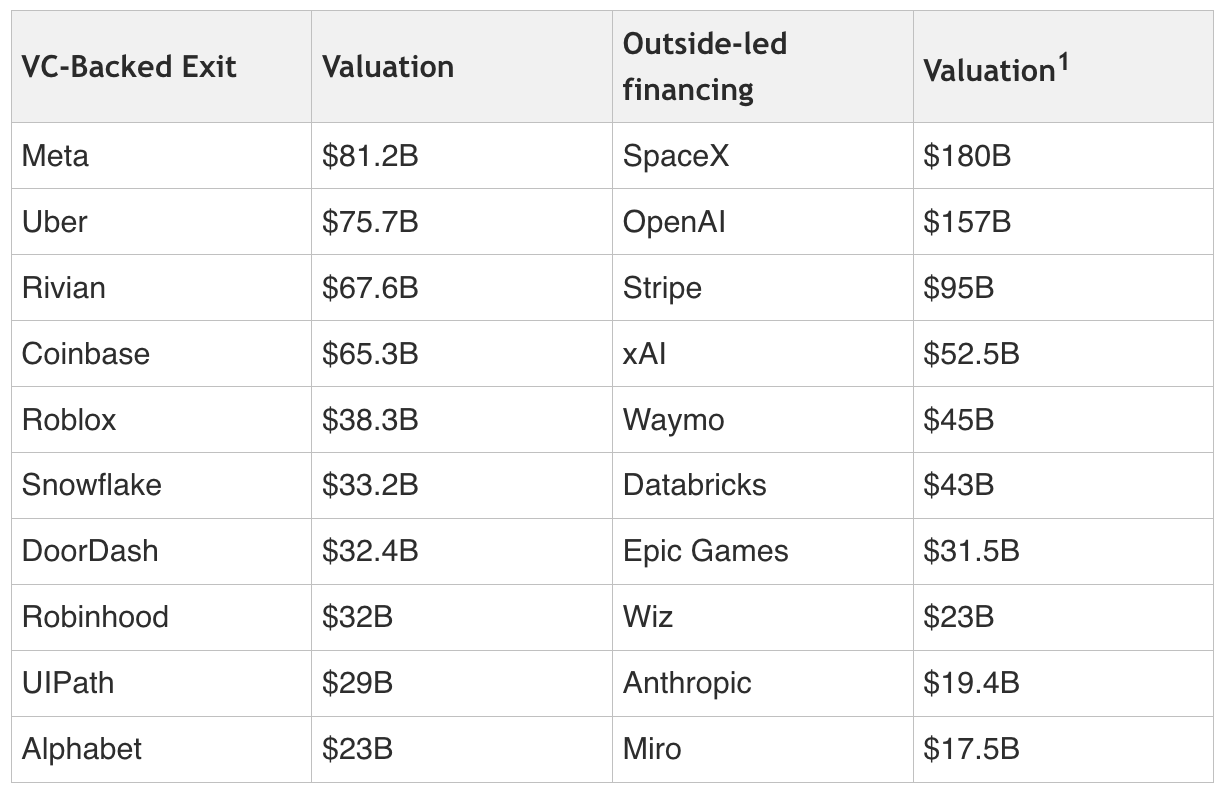

Visualising $160 billion in Exit Value

To put this into perspective, even if the fund had secured early investments in both Meta and Uber — the two largest VC-backed IPOs in history — it still wouldn’t have met the mark. A $5 billion series of funds would need to have owned both, retained a 10% stake at exit, and still have been able to outbid Facebook by threefold for Instagram. That’s how extraordinarily high the bar is set.

The scale of outcomes required isn’t just rare — it is without precedent. It creates a significant execution risk, as the sheer scale of returns needed surpasses anything historically achieved. Yet, the full impact of the funds being raised today won’t be realised for another decade; the feedback loop in venture is extremely long. If that sounds concerning, it only gets worse.

The Exit Market Reality

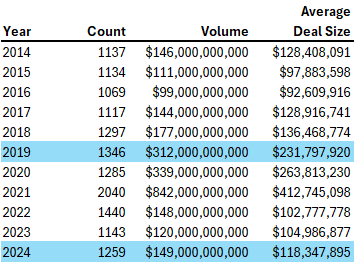

Even if these investors could, in theory, achieve such monumental successes — or string together enough of them — the realities of the exit environment are working against them. In 2019, the average venture-backed exit size was $232 million. By 2024, that had dropped to $118 million, a 96% decline. Even the biggest liquidity moment in recent history (2021) provided an average exit value of $412 million.

The overwhelming majority of exits are modest, and even the best players in the game pick the wrong company more times than not. In reality, exits skew small, yet large funds inherently depend on far larger outcomes merely to return investors’ capital. The schism between the returns VC demands and what the market can realistically deliver only continues to widen; at a certain point, this ceases to be a strategy and becomes little more than wishful thinking.

The Incentive Problem

There’s a certain irony in starting with a set of numbers to qualitatively reason. There’s also a certain irony in that even if these funds could hit their targets, the people running them might not care enough to try.

Assuming a traditional 2/20 fee structure, a $5 billion series of funds will generate $1 billion in management fees over its lifetime. The firm would need $110 billion in exit value to earn the same amount from carry — not quite the full $160 billion needed for a true venture-level underwriting, but still wildly ambitious.

In other words, if they do absolutely nothing, they make a fortune. If they do some of the hardest things that have ever been done in venture capital — for example, owning 10% at IPO in DoorDash, Snowflake (the largest ever SaaS IPO), Robinhood and UiPath — they make about the same. Laid out this clearly, it becomes glaringly obvious that the industry is facing a severe incentive problem.

Founders are Taking Note

Venture capital is fundamentally a business of relationships, and founders are taking notice. They can discern when an investor is genuinely aligned with their success and when they are merely accumulating fees. More importantly, they understand that when challenges inevitably arise, their investors’ true incentives will determine how hard they fight to fix the problem.

Given this, founders are increasingly gravitating toward investors who are actively in the trenches with them, rather than those merely overseeing financial products which are growing at an unprecedented scale.

When the Math Breaks, So Does the Game

The crux of the problem is thus that the math doesn’t work, the exits don’t exist, and the incentives break down. At best, large funds will deliver private equity-style outcomes, albeit with greater risk and illiquidity. They will take huge bets on a shrinking pool of potential outliers, and when they fall short, the result won’t be catastrophic — it will be mediocrity.

Venture capital was never meant to be a game of mediocrity. The best investors in this industry go to war for their companies, fight for the right deals, and support companies to deliver returns that make the risk worthwhile.

But at a certain scale, the structure itself stops allowing for that. The numbers don’t add up. When the math stops working, so does the game.